Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) consists of Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC)—two chronic, immune-mediated disorders of the gastrointestinal tract. While their clinical presentations may overlap, their underlying mechanisms, immune responses, and structural involvement differ significantly.

📈 Prevalence and Epidemiology in Australia

Inflammatory bowel disease is a growing public health concern in Australia, with one of the highest prevalence rates globally. More than 100,000 Australians are currently living with IBD, and this number is rising steadily. The disease most commonly presents in young adults aged 15–35, with increasing incidence in childhood and adolescence. Although the exact cause of this rise is unclear, contributing factors may include Westernised diets, reduced microbial diversity, increased antibiotic exposure in early life, and urban living. The rising prevalence of IBD in developed countries like Australia reflects both improved diagnostic recognition and potential environmental influences on immune tolerance.

👉 This context highlights the importance of understanding IBD pathophysiology early in medical training, given its increasing burden and lifelong impact.

1. Breakdown of Immune Tolerance in the Gut

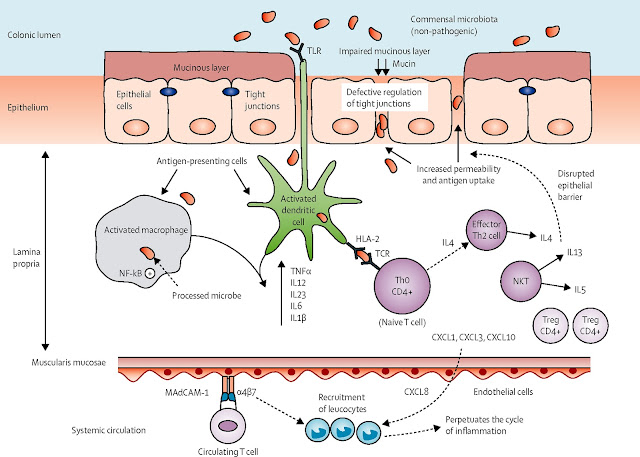

A hallmark of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is the loss of immunological tolerance to intestinal microbiota. The gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT) plays a critical role in distinguishing between harmful pathogens and commensal organisms, ensuring that immune responses remain controlled and non-destructive. Under normal circumstances, regulatory T cells (Tregs) suppress excessive activation of pro-inflammatory pathways, maintaining intestinal homeostasis. Additionally, intestinal epithelial cells secrete mucin, antimicrobial peptides, and IgA, reinforcing barrier integrity and preventing bacterial translocation into underlying tissues.

In IBD, however, this delicate balance is disrupted. Defective Treg function, combined with excessive Th1 and Th17 activation in Crohn’s disease or Th2-driven responses in ulcerative colitis, leads to uncontrolled inflammation. Innate immune dysregulation, including excessive macrophage and dendritic cell activity, results in an overproduction of TNF-α, IL-23, and interferon-gamma, perpetuating chronic mucosal damage. Furthermore, alterations in gut microbiota composition (dysbiosis)—characterized by a reduction in butyrate-producing bacteria and an increase in pathogenic strains—exacerbate epithelial dysfunction, allowing microbial products to breach the intestinal barrier and further stimulate immune responses.

This ongoing cycle of immune activation, epithelial compromise, and dysbiosis contributes to persistent intestinal inflammation, histological damage, and the clinical manifestations of IBD, including chronic diarrhoea, abdominal pain, and nutritional deficiencies.

For more on the immune tolerance and the development of autoimmune disease click for this related post.

Key Immune Pathways Driving Inflammation

- Crohn’s Disease (CD): Dominated by Th1 and Th17-driven inflammation, with excessive production of IL-12, IL-23, and interferon-gamma (IFN-γ). This drives non-caseating granuloma formation, characteristic of CD histopathology.

- Ulcerative Colitis (UC): Largely Th2-mediated, driven by IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13, leading to epithelial barrier dysfunction and mucosal ulceration. (However, UC is not classically Th2-driven like allergy but has Th2-like cytokines (IL-5, IL-13).)

💊 Therapeutic Targets and Immune Pathways

- Anti-TNF agents (e.g., infliximab, adalimumab) inhibit tumour necrosis factor-alpha, dampening Th1-mediated inflammation in Crohn’s.

- Ustekinumab blocks IL-12 and IL-23, targeting both Th1 and Th17 pathways.

- Vedolizumab is a gut-selective integrin inhibitor that prevents lymphocyte trafficking into the gut mucosa, reducing systemic immunosuppression.

2. Inflammatory Mediators and Molecular Mechanisms

The cytokine dysregulation observed in IBD perpetuates inflammation and leads to structural gut damage:

3. Structural and Histopathological Features

Histological examination plays a crucial role in distinguishing Crohn’s disease (CD) vs ulcerative colitis (UC) and in assessing disease severity.

Crohn’s Disease

- 🔬 Transmural inflammation → Extends through all layers of the intestinal wall, leading to fibrosis and structural complications.

- 🔬 Non-caseating granulomas → Aggregates of macrophages, often multinucleated giant cells, forming in response to chronic immune activation.

- 🔬 Skip lesions → Patchy mucosal damage with regions of normal tissue interspersed between inflamed areas.

- 🔬 Deep fissuring ulcers → Leads to cobblestone mucosa, strictures, and risk of fistula formation

Ulcerative Colitis

- 🔬 Superficial mucosal inflammation → Confined to the mucosa and submucosa, sparing deeper layers.

- 🔬 Crypt abscesses → Collection of neutrophils within distorted glandular architecture, a hallmark feature of UC.

- 🔬 Loss of goblet cells → Reduced mucin production, weakening barrier integrity and worsening inflammation.

- 🔬 Continuous disease involvement → Inflammation spreads proximal from the rectum, distinguishing UC from CD’s segmental lesions.

Epithelial Barrier Dysfunction

- Tight junction dysfunction → Reduced expression of occludin and claudins impairs mucosal protection.

- Mucin depletion → Loss of MUC2 expression increases exposure of luminal antigens to the immune system.

- Paneth cell dysfunction (Crohn’s) → Defective secretion of antimicrobial peptides (defensins) contributes to dysbiosis. (Paneth cells are located in the crypts of the small intestine and are a key part of innate mucosal immunity.)

Microvascular & Ischaemic Contributions

- Chronic inflammation disrupts microcirculation, leading to capillary thrombosis, hypoxia, and oxidative stress.

- UC patients can develop vascular congestion with neutrophilic infiltration, worsening mucosal erosion.

4. Genetic and Environmental Contributions

Genetic Risk:

- NOD2 mutations increase susceptibility to Crohn’s disease, impacting bacterial recognition.

- HLA alleles (particularly HLA-DRB1) are implicated in ulcerative colitis.

Environmental Factors:

- Microbiota dysbiosis: Alterations in gut microbial diversity reduce butyrate-producing bacteria, impairing intestinal barrier integrity.

- Smoking paradox: Worsens Crohn’s disease but reduces UC severity.

- Dietary triggers: High-fat diets and emulsifiers exacerbate gut inflammation.

🩻 Extra-Intestinal Manifestations of IBD

- Peripheral arthritis: Usually non-erosive, affecting large joints such as knees and ankles.

- Axial involvement: Sacroiliitis and ankylosing spondylitis, often associated with HLA-B27.

- Erythema nodosum: Painful, red nodules typically on the shins—more common in women.

- Pyoderma gangrenosum: Deep ulcerating lesions, often triggered by trauma (pathergy).

- Episcleritis: Mild, self-limited redness and irritation.

- Uveitis: More serious; may present with pain, photophobia, and vision changes—requires urgent ophthalmology referral.

- Primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC): Chronic cholestatic liver disease more common in UC; increases risk of cholangiocarcinoma.

🩺 Clinical Application: Diagnosing IBD in Practice

Case Presentation

You are a medical student doing a rotation in the gastroenterology clinic. A 22-year-old male, Josh, presents with persistent diarrhoea, abdominal pain, and unintentional weight loss over the past six months. He reports intermittent bloody stools and says he often wakes up at night needing to defecate.

His past history is unremarkable, but he has a strong family history of autoimmune disease. He is a non-smoker and denies recent travel or infectious exposure.

Examination Findings

- Vitals: Temp: 37.6°C, HR: 96 bpm, BP: 118/78 mmHg

- Abdominal exam: Mild tenderness in the right lower quadrant, no rebound tenderness

- Perianal inspection: Presence of skin tags and a small fistula

- Routine blood tests:

- Hb: 10.8 g/dL (low)

- CRP: 24 mg/L (elevated)

- Albumin: 32 g/L (low)

- Faecal calprotectin: 680 μg/g (high)

Clinical Question

Based on Josh’s presentation, examination, and investigations, what is the most likely diagnosis? How would you confirm it?

5. Diagnostic Criteria for IBD

IBD is diagnosed based on a combination of clinical presentation, laboratory markers, imaging, and histopathology.

Differentiating Crohn’s Disease vs Ulcerative Colitis

Malabsorption in Crohn’s Disease

In Crohn’s disease, inflammation extends through the full thickness of the intestinal wall (transmural involvement), which can disrupt normal nutrient absorption. The most affected regions are the terminal ileum and proximal small bowel, leading to specific malabsorption syndromes.

Key Nutritional Deficiencies in Crohn’s Disease

Pathophysiological Mechanisms of Malabsorption

- Mucosal Damage & Inflammation → Impaired villi function, reducing absorption efficiency.

- Intestinal Fistulas & Strictures → Alter nutrient transit, limiting digestion.

- Resection or Bowel Shortening → Patients with previous surgeries have reduced functional absorption area.

- Bile Acid Wasting → Impaired fat digestion leads to steatorrhoea, fat-soluble vitamin deficiencies, and gallstone formation.

Investigations to Confirm Diagnosis

- Colonoscopy with biopsy → Identifies inflammation pattern and confirms histopathology

- Faecal calprotectin → Elevated in IBD, distinguishing from IBS

- CT/MRI enterography → Detects small bowel involvement (important for Crohn’s)

- Blood tests → Anaemia (common in CD), hypoalbuminaemia (suggests malabsorption), elevated CRP

Final Diagnosis for Josh?

Given Josh’s clinical signs (RLQ pain, weight loss, perianal fistula) and investigations (anaemia, elevated inflammatory markers, high faecal calprotectin), Crohn’s disease is the most likely diagnosis.

Takeaways & Clinical Pearls

Key Concepts

✔ IBD is an immune-mediated disorder characterised by chronic intestinal inflammation due to dysregulated tolerance to gut microbiota.

✔ Crohn’s disease involves transmural inflammation, granulomas, and skip lesions, whereas ulcerative colitis presents with mucosal-only, continuous colonic involvement.

✔ The Th1/Th17 axis dominates Crohn’s, while Th2 cytokines drive ulcerative colitis. TNF-α inhibitors and IL-23 blockers are key therapeutic targets.

✔ Histopathology and imaging are essential for distinguishing deep ulcers and strictures in Crohn’s vs. crypt abscesses and loss of haustration in UC.

Clinical Pearls

Inflammatory bowel disease is a prime example of how disrupted immune tolerance can lead to chronic inflammation and systemic disease. By understanding its pathophysiology, students can begin to connect immunology, clinical features, and therapeutic strategies—building a foundation for future practice.

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment