Infections in the renal system are among the most common reasons patients present to GPs and emergency departments — yet their underlying mechanisms are often oversimplified. These aren't just “bladder bugs” causing discomfort: they are dynamic, evolving conditions that reflect an interplay between microbial virulence, host defence, and anatomical vulnerabilities.

From the relatively straightforward presentation of cystitis to the more serious implications of pyelonephritis, renal infections provide a perfect lens through which to explore the clinical relevance of physiology and pathophysiology. How does a bacterium from the gut end up damaging a kidney? What determines whether a simple UTI becomes a systemic illness? And how do we decide when antibiotics, imaging, or hospital admission are truly necessary?

In this post, we’ll explore how renal infections arise, what differentiates upper from lower tract involvement, and how pathophysiological principles guide investigation and treatment decisions.

1 1. The Spectrum: From Cystitis to Pyelonephritis

Urinary tract infections (UTIs)

are often discussed as a single entity, but they actually represent a spectrum

of disease — from localised irritation of the bladder to more serious

infections involving the kidneys. Understanding where the infection sits

helps explain how it presents and why it matters.

💡 Lower Urinary Tract Infection (Cystitis)

When infection remains confined to the bladder, it typically causes:

- Dysuria

(pain or burning on urination)

- Frequency

and urgency, due to inflammation of the bladder wall

- Suprapubic

discomfort, often described as a pressure or heaviness

- Haematuria-

either macroscopic (visible blood) or microscopic, picked up on

dipstick or microscopy

- No

systemic features — the patient usually feels otherwise well

This is the classic “uncomplicated

UTI,” most commonly seen in healthy women.

🔺 Upper Urinary Tract Infection (Pyelonephritis)

If bacteria ascend via the ureters

and reach the renal pelvis or parenchyma, the infection becomes more serious.

The clinical picture shifts to include:

- Fever,

often with rigors

- Flank

or loin pain, due to inflammation around the kidney

- Nausea

or vomiting, reflecting systemic illness

- Sometimes

lower tract symptoms, but not always

The infection now involves a

well-perfused organ — the kidney — making bacteraemia and sepsis more

likely if left untreated. This is why pyelonephritis warrants early recognition

and prompt management.

|

Site |

Typical Features |

|

Lower urinary tract (e.g. cystitis) |

Dysuria, frequency, urgency, suprapubic discomfort. Systemically

well. |

|

Upper urinary tract (e.g. pyelonephritis) |

Fever, loin or flank pain, nausea/vomiting, systemic signs. ± Lower

tract symptoms. |

2. Host Defence and Renal Vulnerability

Despite being connected to the

outside world, the urinary tract is remarkably good at defending itself from

infection. In fact, most people produce litres of urine every day without ever

developing a UTI. That’s thanks to a combination of mechanical flushing,

chemical composition, anatomical barriers, and immune vigilance.

🧪 Natural Defences

- Urine

is not a welcoming place for bacteria: it's slightly acidic, has a

high urea concentration, and lacks nutrients. These properties inhibit

bacterial growth.

- Regular

voiding flushes pathogens from the bladder before they can adhere to

the urothelium and colonise.

- Urothelial

cells express antimicrobial peptides and can initiate immune responses

when invaded.

But as robust as this system is,

it's not infallible — and several factors can tip the balance in favour of

infection.

🛠️ Anatomical and Mechanical Factors

- The

female urethra is short and closer to the anus, making it easier

for enteric bacteria (like E. coli) to access the bladder. This

explains why UTIs are significantly more common in women.

- Catheterisation

bypasses the urethral defence entirely, creating a direct path for

bacteria to ascend and form biofilms.

- Vesicoureteric

reflux (VUR) — a condition where urine flows backward from the bladder

into the ureters — can carry bacteria up into the kidneys. VUR is

particularly relevant in children with recurrent UTIs.

- Urinary

tract obstruction (e.g. due to stones, strictures, or enlarged

prostate) leads to stasis — and stagnant urine is a prime breeding ground

for infection.

🌡️ Systemic Host Factors

Certain physiological or disease

states reduce resistance to infection:

- Pregnancy

leads to dilated ureters and reduced bladder tone, promoting stasis and

increasing the risk of pyelonephritis.

- Diabetes

mellitus impairs immune responses and may cause glycosuria, creating

an inviting environment for bacterial growth.

- Immunosuppression, whether due to medications or conditions like HIV, weakens the body's ability to contain infection once it begins.

🧠 Takeaway: The

urinary tract has robust defences, but infections occur when bacteria either

bypass those barriers or the host is unable to mount an adequate response.

Knowing who is at risk — and why — is key to early recognition and appropriate

management.

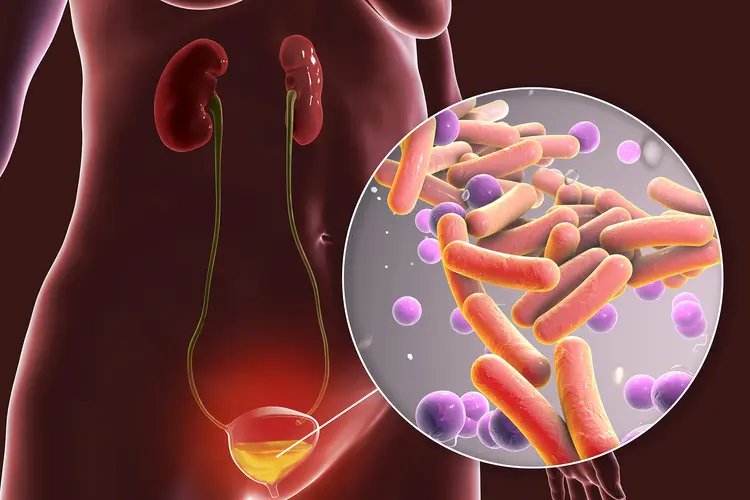

3. Uropathogens: Not Just a List

Many urinary tract infections are

caused by a familiar cast of bacteria, but what makes one organism succeed

where others don’t? To understand clinical patterns — who gets sick, how they

present, and why some infections persist — it’s worth exploring the microbes

through the lens of colonisation, adhesion, and immune evasion.

💩 Escherichia coli: The Opportunistic Local

E. coli causes about 75–90%

of community-acquired UTIs — but it’s not just there by chance. This

gut-dwelling Gram-negative rod possesses a series of tools that help it survive

and thrive in the urinary tract:

- Adhesins

(like P fimbriae) allow E. coli to latch onto uroepithelial cells

and resist the flushing effects of urine.

- Type

I fimbriae mediate initial bladder colonisation, while P fimbriae

are associated with pyelonephritis.

- It

can form biofilms on uroepithelium or catheters, allowing

persistence and resistance to immune clearance.

- Some

strains have capsules that block phagocytosis and reduce immune

detection.

🧠 Takeaway: The

dominance of E. coli isn’t accidental — it reflects its evolved ability

to bind, hide, and persist in a hostile environment.

🦠 Klebsiella & Proteus: The Opportunists

These Gram-negative rods are less

common in uncomplicated UTIs but become more prominent in:

- Recurrent

infections

- Structural

abnormalities

- Urinary

stasis or obstruction

🧠 Clinical clue: A

patient with recurrent UTIs, alkaline urine, and staghorn calculi? Think

Proteus.

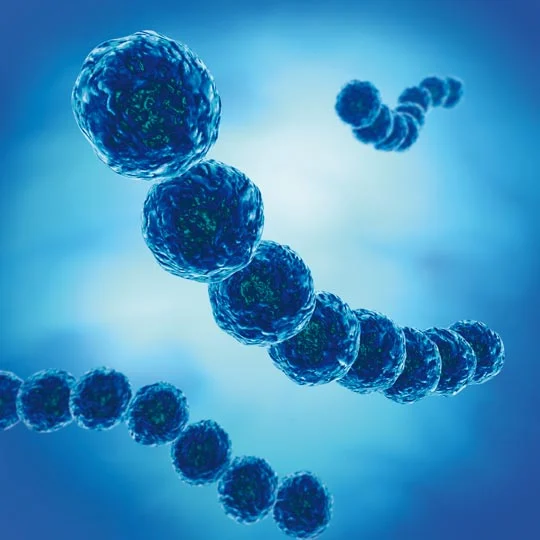

🧫 Enterococcus: The Catheter Survivor

This Gram-positive cocci is part of normal gut flora but becomes more relevant in:- Hospital-acquired

UTIs

- Catheter-associated

infections

- Immunocompromised

hosts

🧠 Clinical point:

Not all urinary bugs are Gram-negative — Gram-positives like Enterococcus

signal a shift in setting, risk factors, or equipment.

🌸 Staphylococcus saprophyticus: The Specialist

While often overlooked, S.

saprophyticus is a coagulase-negative staph that specifically

affects:

- Young,

sexually active women

- Often

causes acute uncomplicated cystitis

- Lacks

dramatic virulence, but adheres well to urothelium and often escapes

immune clearance without systemic signs

🧠 Pearl: In young

women with cystitis but negative nitrites on dipstick, S. saprophyticus

is a common culprit — it doesn’t reduce nitrates like E. coli does.

|

Common Organisms |

Comments |

|

Escherichia coli |

Most common (esp. community-acquired); faecal origin |

|

Klebsiella, Proteus |

More common in recurrent or structural abnormality |

|

Enterococcus |

Often hospital-acquired or catheter-related |

|

Staphylococcus saprophyticus |

Seen in young, sexually active females |

🦠 Proteus species

can alkalinise urine → predispose to struvite stones

🧠 Thinking Beyond the Bladder: When UTI Isn’t So Simple

Before diving into treatment,

especially in patients with recurrent UTIs or unusual symptoms, take a step

back and ask:

- Is

there an anatomical cause?

Think obstruction (e.g. stone, stricture), reflux, incomplete emptying — any factor that impairs normal urine flow can create a breeding ground for infection. - Is

this truly a UTI?

Not all dysuria is infectious. Consider STIs, vaginal atrophy, or interstitial cystitis — especially if there’s sterile pyuria or treatment failure. - Are

they responding to treatment as expected?

If symptoms persist beyond 48–72 hours or recur soon after antibiotics, investigate further: wrong bug? Wrong drug? Or a deeper problem?

While most UTIs are straightforward, not all that burns is

cystitis, and not all infection is simple.

|

Flag |

Consider |

|

Male patient with UTI |

Investigate for urinary obstruction, prostatitis, or structural

abnormality |

|

Sterile pyuria (white cells but no bacteria) |

STI, interstitial cystitis, renal TB (rare), contamination |

|

Recurrent infections |

Reflux, stones, incomplete bladder emptying, diabetes |

|

No improvement after 48–72 hours |

Resistant organism, incorrect diagnosis, renal involvement |

|

Atypical symptoms (e.g. flank mass, persistent fever) |

Obstruction, abscess, or alternative pathology (e.g. malignancy) |

🧠 Tip for students:

Any time something feels “off-script” in a UTI presentation, pause and ask — is

this a red flag, or just a variation on the usual

4. Management Principles

When it comes to urinary tract

infections, effective management begins with recognising where the

infection is, how sick the patient is, and what host factors

might complicate its course. Diagnosis and treatment decisions are rooted in

understanding the bacterial burden, the host’s defences, and the risk of

progression.

🧪 Diagnosis

Urinalysis is the

first-line tool for bedside diagnosis:

- Leukocytes

(white blood cells) suggest inflammatory response in the urinary tract.

- Nitrites

are formed when certain bacteria (notably E. coli) convert urinary

nitrates — a useful indirect marker of Gram-negative infection.

- Microscopic

or macroscopic haematuria may reflect urothelial irritation,

particularly in cystitis.

These clues help identify

infection but do not replace clinical judgement — especially in older patients

or those with atypical presentations.

Urine culture becomes

essential when:

- The

patient is systemically unwell (e.g. pyelonephritis)

- The

presentation is atypical, recurrent, or in men (who

typically don’t get UTIs unless something else is going on)

- There's

concern for antibiotic resistance (e.g. recent hospitalisation or

travel, or prior resistant organisms)

- You’re

not sure if it’s truly a UTI or another condition mimicking

symptoms

Cultures confirm the organism and

its sensitivities — critical for tailoring therapy in complicated cases.

💊 Pharmacological Management:

The right drug, for the right bug, in the right tissue — at the right time.

Uncomplicated Cystitis (in nonpregnant adults)

- Generally

treated empirically with a short course of oral antibiotics (e.g. trimethoprim,

nitrofurantoin)

- Rationale:

These patients are systemically well, the likely pathogen is predictable (E.

coli), and the infection is localised.

First-line options (per eTG):

- Trimethoprim 300 mg orally, daily for 3

days

- Nitrofurantoin 100 mg orally, every 6

hours for 5 days

Why these?

- Both are narrow-spectrum

agents that concentrate well in the bladder.

- Despite 20% resistance to

trimethoprim in E. coli, it's still first-line because treatment

failure in otherwise well patients is uncommon — and the broader aim is to

avoid unnecessary use of broader-spectrum agents.

- Nitrofurantoin remains

effective but depends on adequate renal function (eGFR >30 mL/min) to

concentrate in the urine.

When to avoid:

- Nitrofurantoin should not

be used for suspected pyelonephritis — it doesn’t reach renal

tissue at therapeutic levels.

- Always review allergies and

potential for pregnancy.

Pyelonephritis: Depth of Infection, Depth of Treatment

· Rationale: Prompt bactericidal treatment reduces risk of bacteraemia, sepsis, and permanent renal damage.

|

Clinical status |

Recommended empirical

treatment |

Why this choice? |

|

Mild/moderate, systemically well |

Oral amoxicillin + clavulanate |

Good oral bioavailability and

tissue penetration; covers E. coli and other Gram-negatives |

|

Penicillin allergy (non-severe) |

Oral ciprofloxacin |

Excellent renal penetration;

used cautiously due to risk of resistance and collateral damage |

|

Systemically unwell (fever

≥38°C, vomiting, sepsis) |

IV gentamicin plus IV

amoxicillin or ampicillin |

Gentamicin provides broad

Gram-negative coverage; amoxicillin adds Enterococcus and

Gram-positive coverage. Rapid IV delivery matches the clinical urgency. |

🧠

Why not nitrofurantoin or fosfomycin?

These drugs do not achieve adequate concentrations in kidney tissue and are not

appropriate for infections above the bladder.

💡

First-year insight: We choose antibiotics based not just on the bug, but

on the depth of infection, the tissue involved, and the risk

of deterioration. A cystitis can fail to improve with trimethoprim, and

that’s okay — but starting the wrong agent in pyelonephritis can delay

clearance, allow sepsis, and harm the kidney itself.

Warnings

- Many

antimicrobials are renally excreted or nephrotoxic at high doses.

- Always check renal function before prescribing — particularly for aminoglycosides (eg gentamycin), which are effective but potentially nephrotoxic

Gentamicin is a potent aminoglycoside antibiotic often used in severe pyelonephritis. It’s rapidly bactericidal against Gram-negative organisms like E. coli and concentrates well in renal tissue — exactly what’s needed in serious kidney infections.

But there’s a catch:

- Gentamicin is nephrotoxic and ototoxic, particularly when:

- Dosed incorrectly

- Given for prolonged periods

- Used in patients with impaired renal function or volume depletion

📚 First-year insight: Aminoglycosides are lifesaving in the right context — but like many powerful tools, they demand respect and close monitoring.

⚠️ Recognise Red Flags

Certain features suggest the

infection is no longer confined to the urinary tract:

- Persistent

vomiting → can’t absorb oral meds

- Rising

creatinine → may indicate urosepsis or obstructive uropathy

- Hypotension,

tachycardia, or rigors → systemic inflammatory response

- Flank

pain worsening despite treatment → consider abscess or obstruction

🧠 These patients need

escalation — often to hospital care for IV fluids, imaging, and close

monitoring.

💧 Non-Pharmacological Management: Supporting the System

While antibiotics are the

cornerstone of treatment, several supportive measures can ease symptoms,

promote recovery, and reduce recurrence — especially in uncomplicated lower

UTIs.

🥤 Fluids

- Encouraging

adequate hydration helps dilute urine and promotes frequent voiding,

which can mechanically flush bacteria from the bladder.

- There’s

no magic volume, but aiming for clear or pale yellow urine is a

practical guide.

- In

pyelonephritis or systemic illness, IV fluids may be needed to

support perfusion and renal function.

🧠 Caution:

Overhydration doesn’t “cure” infection and may worsen hyponatraemia in

vulnerable patients — especially the elderly.

💊 Pain Relief: Targeting Inflammation

- Paracetamol

is first-line for dysuria and suprapubic discomfort.

- NSAIDs

(e.g. ibuprofen) may help with inflammation and fever, but use with

caution in patients with impaired renal function or dehydration.

- Phenazopyridine

(not widely used in Australia) is a urinary tract analgesic that can

relieve dysuria but may mask worsening symptoms.

NSAIDs (like ibuprofen) are helpful for fever and dysuria in UTIs — but they reduce prostaglandin synthesis, which in turn decreases afferent arteriole dilation.

- In healthy people, NSAIDs are usually well tolerated

- But in someone who’s volume-depleted (e.g. due to fever, vomiting, pyelonephritis), NSAIDs may reduce renal perfusion and cause acute kidney injury

- Risk is highest in the “triple whammy” of NSAID + ACE inhibitor + diuretic

🧪 Urinary Alkalisers:

Comfort, Not Cure

- Products

like sodium citrate or potassium citrate can reduce urinary

acidity, which may ease dysuria.

- They

do not treat infection and should be used as adjuncts only.

- Avoid

in patients with renal impairment or those on sodium-restricted diets.

🍒 Cranberry Products:

Prevention, Not Treatment

Cranberries have long been

promoted for UTI prevention — but what does the evidence say?

A 2023 Cochrane

review found that cranberry juice or supplements can reduce the risk of

recurrent UTIs in women, children, and people at higher risk (e.g.

post-catheterisation). The proposed mechanism is that proanthocyanidins

in cranberries inhibit E. coli from adhering to the bladder wall.

- The

benefit is preventive, not therapeutic — cranberry products do

not treat active infections.

- There’s

no proven benefit in elderly patients, pregnant women, or those

with incomplete bladder emptying.

- Products

vary in concentration and formulation, making dosing inconsistent.

🧠 Bottom line: Cranberry may help reduce recurrence in select groups, but it’s not a substitute for antibiotics when infection is present. It is harmless however, and if it encourages people to drink more fluids then that alone may help infection.

Nitrofurantoin works best in acidic urine (low pH).

Urinary alkalinisers (like Ural, Citravescent, or potassium citrate) raise urinary pH, making the environment less favourable for nitrofurantoin and potentially reducing its effectiveness.

🧠 Takeaway: If a patient is prescribed nitrofurantoin, avoid using urinary alkalisers during the same treatment course — reach for paracetamol instead for dysuria relief.

🩺 Clinical Case: A Chilling Flank

A 36-year-old woman presents with

2 days of fever, rigors, left flank pain, and nausea. She also reports urinary

frequency and dysuria. On examination, her temperature is 38.9°C and there’s

tenderness over her left costovertebral angle. Her BP is 106/64 mmHg, HR 102

bpm.

Urinalysis:

- Positive

for leukocytes and nitrites

- Moderate

haematuria

Blood tests:

- WCC:

14.2 ×10⁹/L (↑)

- Creatinine:

98 µmol/L (normal)

- CRP:

180 mg/L (↑)

She is diagnosed with acute

pyelonephritis and started on intravenous ceftriaxone.

🧠 Reflection questions

- What clues point toward an upper tract infection in this patient?

- Why is a urine culture important in this case?

- What host factors may increase the risk of progression from lower to upper tract infection?

· Anatomical issues like vesicoureteric

reflux or obstruction (e.g. stone, tumour, or enlarged prostate)

·

Immunosuppression, whether due to disease

or therapy, weakens systemic response to early infection

·

Pregnancy alters ureteral tone and flow,

promoting stasis

·

Delays in diagnosis or treatment allow

organisms to multiply and ascend unchallenged

🧠

In this patient’s case, even without comorbidities, a short delay in seeking

care may have allowed progression — a reminder that host vulnerability is often

dynamic, not fixed

- Why start with IV antibiotics?

⏭️ What Next? Monitoring and Moving Forward

Once a patient with pyelonephritis

is started on IV antibiotics, management decisions don’t stop — they evolve.

Here's how to think about the next steps:

🧪 1. Review Culture Results

- Tailor

antibiotics based on sensitivity patterns — especially if initial

therapy was empirical.

- If

E. coli is confirmed and sensitive to oral agents, consider stepping

down to oral therapy once the patient improves clinically (afebrile,

tolerating fluids, stable vitals).

💊 2. Step Down (When Ready)

- Patients

can be switched to oral antibiotics once they:

- Have

been afebrile for at least 24 hours

- Can

tolerate oral intake

- Are clinically improving

- Total

duration is usually 10–14 days, including both IV and oral phases.

🧠 3. Ask Why It Happened

Even if the episode resolves,

always ask:

- Was

there a delay in presentation or diagnosis?

- Is

this a first-time infection, or are there signs of recurrence?

- Could

pregnancy, diabetes, obstruction, or reflux be contributing?

- Should

the patient have a renal ultrasound, particularly if not improving,

or if this isn’t their first episode?

📆 4. Plan Follow-Up

- Organise

GP review post-discharge with culture results and antibiotic plan.

- For

recurrent infections or unclear cause, consider referral for urological

imaging or specialist input.

🧠 Final pearl:

Management doesn’t stop at symptom resolution — it’s also about making sure

this doesn’t happen again, and knowing when an “ordinary UTI” might be masking

something more.

🔁 Reflection Prompts: Sense-Making, Not Memorising

Use these to test your clinical

reasoning — not just whether you know the facts, but whether you understand why

they matter.

- How

does the presentation of pyelonephritis differ from cystitis — and what

does this tell you about the depth of infection?

- Why

might patients with diabetes or pregnancy be more vulnerable to ascending

renal infections?

- How

does the body attempt to defend against urinary tract infections — and

what factors can overcome these defences?

- What

are the risks of delaying appropriate treatment in upper UTIs?

- How

do you match the severity of illness to your route and choice of

antibiotics?

🧠 Tip: If you can

talk through these aloud or teach them to a peer, you're not just learning —

you're building your diagnostic intuition.

🧵 Wrapping It Up: Beyond Bugs and Drugs

Urinary tract infections might

seem simple — common, familiar, easily treated. But as you’ve now seen, they

offer a rich chance to practise thinking like a clinician:

- To

ask not just what the diagnosis is, but why this patient got

sick at this moment

- To

choose treatment that’s not just “by the book,” but right for this

tissue, this bug, and this host

- To

recognise that sometimes, what looks like a UTI is actually something

more — or something different

Whether it’s understanding why

nitrofurantoin won’t work in pyelonephritis, spotting sterile pyuria in an STI,

or matching IV therapy to systemic signs — the goal isn’t just to memorise

facts. It’s to build a habit of clear, conscious clinical reasoning that

flexes with context.

No comments:

Post a Comment